For those entrusted with the stewardship of offshore oil and gas facilities, Asset Integrity Management (AIM) is more than a set of procedures; it is a fundamental philosophy for ensuring safe, reliable, and sustainable operations. These complex structures, constantly assailed by the harsh marine environment, are in a perpetual state of degradation.

Unexpected integrity-related downtime imposes significant and actual costs on the owners and operators of offshore facilities. A primary way to effectively manage the risks associated with offshore degradation is to implement a robust AIM program.

This blog post will explore the primary degradation mechanisms that threaten the integrity of offshore assets: corrosion, fatigue, material degradation, and wear. By understanding the underlying science of these mechanisms, we can better appreciate the challenges of AIM and the importance of a proactive and data-driven approach to managing the integrity of these critical facilities.

Corrosion: The Electrochemical Challenge to Asset Integrity

From an AIM perspective, corrosion is one of the most significant threats to the integrity of an offshore asset. It is an insidious and ever-present electrochemical process that can lead to loss of containment, structural failure, and costly downtime. A comprehensive AIM program must include a detailed understanding of the various corrosion mechanisms at play.

The Electrochemical Corrosion Process

In the marine environment, the corrosion of steel involves two simultaneous reactions occurring on the metal surface:

- Anodic Reaction (Oxidation): At the anode, iron () atoms lose electrons to become ferrous ions ( ). These ions enter the seawater, while the released electrons remain in the metal.

- Cathodic Reaction (Reduction): The free electrons travel through the metal to the cathode. There, they react with dissolved oxygen and water to form hydroxide ions ().

- Formation of Rust: The ferrous ions () and hydroxide ions () combine to form ferrous hydroxide (), which further oxidizes to create the reddish-brown rust known as hydrated ferric oxide ().

The management of corrosion-related risk requires a detailed understanding of the different corrosion zones and their associated corrosion rates:

- Atmospheric Zone: In the upper parts of the platform, corrosion is driven by the deposition of salt spray and atmospheric moisture. The corrosion rate is influenced by factors such as wind speed, humidity, and temperature, and often ranges from 0.1 to 0.4 mm/year.

- Splash Zone: This is the most severely corroded area, experiencing intermittent wetting and drying, which ensures a continuous supply of both oxygen and an electrolyte. The constant wave action can also erode protective coatings, exposing fresh metal to attack. Corrosion rates in the splash zone can often be as high as 1.5 mm/year.

- Submerged Zone: In the continuously submerged parts of the structure, the corrosion rate is primarily controlled by the diffusion of oxygen to the metal surface. As depth increases, the oxygen concentration decreases, leading to a corresponding decrease in the corrosion rate.

- Buried Zone: In the seabed, the corrosion rate is generally low due to the lack of oxygen. However, the presence of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRBs) can lead to significant microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC). These anaerobic bacteria reduce sulfate ions to highly corrosive hydrogen sulfide (H2S), which can lead to rapid localized corrosion.

An effective AIM program must also account for the various forms of localized corrosion, which can be more difficult to predict and manage than uniform corrosion:

- Pitting Corrosion: A particularly insidious form of localized corrosion that creates small, deep pits in the metal surface. These pits can be difficult to detect and can rapidly penetrate the thickness of a pipeline or structural member, leading to unexpected failures.

- Crevice Corrosion: Occurs in confined spaces, such as under gaskets or in the threads of fasteners, where a stagnant solution can become depleted of oxygen and enriched in chloride ions, creating a highly acidic and corrosive microenvironment.

- Galvanic Corrosion: When two dissimilar metals are in electrical contact in an electrolyte, a galvanic cell is formed. The less noble metal (the anode) corrodes at an accelerated rate, while the more noble metal (the cathode) is protected. This is a major concern in complex assemblies with multiple alloys.

- Stress Corrosion Cracking: A brittle failure of a normally ductile material that occurs under the combined action of a tensile stress and a specific corrosive environment. The presence of H2S in sour service environments can lead to sulfide stress cracking, a major concern for high-strength steels.

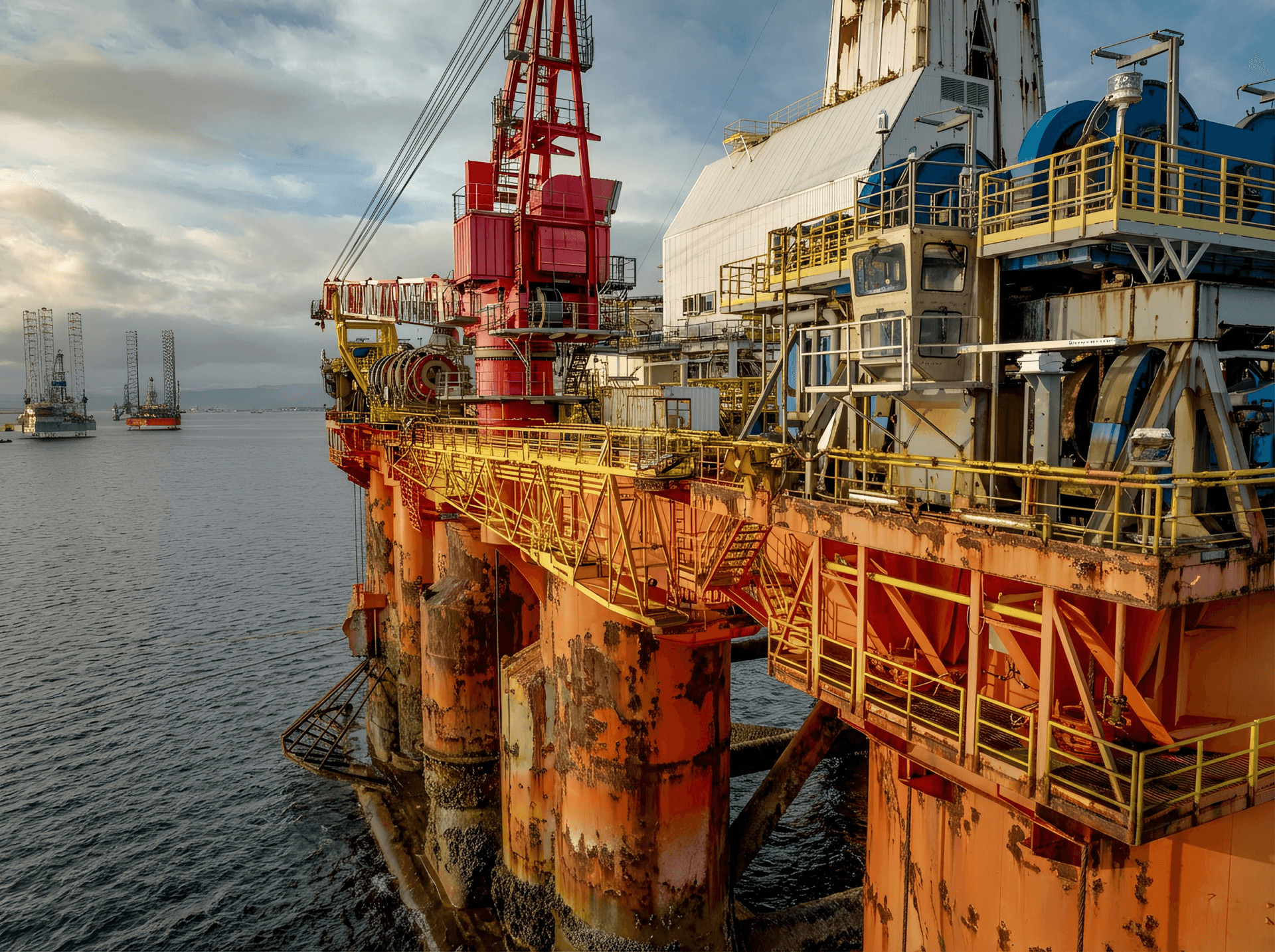

Corrosion on an offshore platform

Fatigue and Fracture: Managing the Integrity of Cyclically Loaded Assets

The dynamic nature of the offshore environment means that structures are constantly subjected to cyclical loading from waves, wind, and currents. From an AIM perspective, this cyclical loading poses a significant threat to the long-term integrity of the asset, as it can lead to the initiation and propagation of fatigue cracks.

The fatigue life of a structural component is typically assessed using an S-N curve, which plots the applied stress range (S) against the number of cycles to failure (N). A key component of any AIM program is a detailed fatigue analysis to ensure that the cumulative damage from all anticipated loading events over the structure’s design life does not exceed its fatigue capacity. The Palmgren-Miner rule is commonly used to calculate cumulative fatigue damage from a spectrum of different stress ranges.

Welded joints are a primary focus for fatigue-related AIM activities, as they act as stress concentration points. The stress concentration factor (SCF) is a measure of the localized increase in stress at a geometric discontinuity, and it is a critical parameter in the fatigue analysis of welded joints. Careful weld profiling and post-weld heat treatment (PWHT) can help to reduce the SCF and improve the fatigue life of a weld.

Once a fatigue crack has initiated, its growth is governed by the principles of fracture mechanics. The Paris Law is a widely used model that relates the rate of crack growth (da/dN) to the stress intensity factor range (ΔK), a parameter that quantifies the magnitude of the stress field at the crack tip. By applying the Paris Law, it is possible to predict the time it will take for a crack to grow from an initial size to a critical size, at which point the remaining ligament of the structure can no longer support the applied load and a fracture occurs.

The synergistic effect of a corrosive environment and cyclical loading, known as corrosion fatigue, is a major challenge for AIM in the offshore industry. The corrosive environment can accelerate both the initiation and propagation of fatigue cracks and often results in a fatigue life which is significantly shorter than what is predicted by standard S-N curves in air, making it a critical consideration in the design and life assessment of offshore structures.

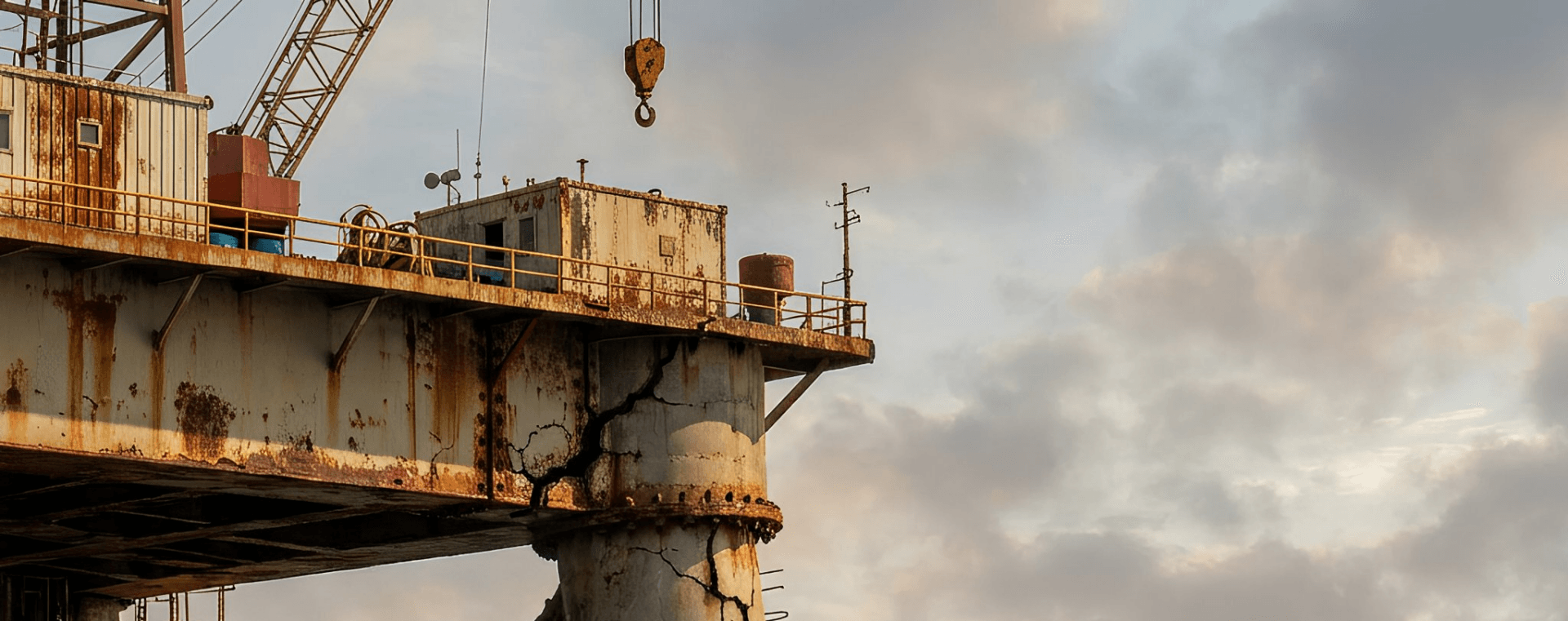

Fatigue crack on an offshore platform

Material Degradation: An AIM Challenge for Non-Metallic Components

A holistic AIM program must extend beyond the primary steel structure to include the wide range of non-metallic materials used in critical applications. These materials, including polymers, composites, and elastomers, are also susceptible to degradation in the marine environment.

Fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) composites are increasingly being used in offshore applications due to their high strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and design flexibility. However, the long-term durability of FRP composites in a marine environment is a major concern for AIM. The polymer matrix can absorb moisture from seawater, leading to a reduction in its mechanical properties, a process known as plasticization, often resulting in a decrease in the glass transition temperature for the material.

The most critical failure mechanism, however, is the degradation of the bond between the reinforcing fibers and the polymer matrix. Water can wick along the fiber-matrix interface, leading to a loss of adhesion and a significant reduction in the composite’s strength and stiffness.

Elastomers, which are used for seals, gaskets, and other flexible components, are also susceptible to degradation. The elevated temperatures and pressures encountered in oil and gas production can cause elastomers to swell, harden, or crack, leading to a loss of sealing integrity. The compatibility of the elastomer with the process fluids is also a critical consideration, as some fluids can cause rapid degradation of the material.

As industry shifts toward greener materials, non-metallics and composites offer corrosion resistance but require comprehensive AIM strategies to mitigate condition-induced failures.

Wear and Erosion: Managing the Integrity of Production Systems

The integrity of the production system is a key focus of any AIM program. The high-velocity flow of multiphase fluids, often containing sand and other solid particles, can cause significant wear and erosion of pipelines, valves, and other process equipment.

Erosion is the mechanical removal of material from a surface by the impingement of solid particles. The rate of erosion is influenced by a number of factors, including the flow velocity, the size and hardness of the particles, and the impingement angle. Erosion-corrosion is a particularly aggressive form of degradation where the abrasive action of the flowing fluid removes the protective corrosion product layer, exposing fresh metal to the corrosive environment. Erosion-corrosion in sand-laden flows demands RBI prioritization in AIM programs to prevent unplanned shutdowns.

Cavitation is another form of wear that can occur in areas of high fluid velocity and low pressure, such as in pumps and valves. When the local pressure drops below the vapor pressure of the liquid, vapor bubbles are formed. These bubbles then collapse when they move into a region of higher pressure, creating a shockwave that can cause damage to the material surface. Technologies like acoustic emissions sensors can detect cavitation early, integrating into digital AIM programs.

The Pillars of a Proactive Asset Integrity Management Program

A proactive AIM program is built on a foundation of robust mitigation and monitoring strategies. These are not simply maintenance activities; they are the core pillars of a data-driven approach to managing the integrity of the asset.

- Material Selection: The first line of defense is the selection of materials that are resistant to the specific degradation mechanisms they will encounter. This may involve the use of corrosion-resistant alloys, such as duplex stainless steels, the application of advanced coatings and linings, or non-metallic materials.

- Risk-Based Inspection (RBI): RBI is a systematic approach to inspection planning that prioritizes inspection efforts based on the risk of failure. This allows operators to focus their resources on the most critical components and to optimize their inspection and maintenance programs. RBI approaches have the potential to harness advanced data analytics to reduce inspection costs while maintaining profitability and safety.

- Advanced Inspection and Monitoring: A comprehensive inspection and monitoring program is essential to detect and track the progression of degradation. This includes a range of non-destructive testing (NDT) techniques, such as ultrasonic testing, radiographic testing, and magnetic particle inspection. Advanced structural health monitoring (SHM) systems, which use a network of sensors to continuously monitor the condition of the structure in real-time, are also being increasingly used.

- Cathodic Protection: Cathodic protection is a widely used technique to control the corrosion of subsea pipelines and structures. This can be achieved using either sacrificial anodes, which are blocks of a more reactive metal (such as aluminum or zinc) that are electrically connected to the structure, or an impressed current system, which uses an external power source to impress a protective current onto the structure.

- Corrosion Inhibitors & Coatings: Corrosion inhibitors are chemicals that are injected into process fluids to reduce the rate of corrosion. They work by forming a protective film on the metal surface or by altering the chemistry of the corrosive environment. Coatings function as barriers or sacrificial layers applied to metal surfaces to prevent degradation from oxidation, moisture, and chemicals. They can include substances such as epoxies, polyurethane, ceramics, zinc-based primers, or galvanization.

- Digital Twins and Predictive Analytics: The rapid growth of machine-learning and AI-based tools together with increased use of IoT sensors to collect process data provides an opportunity to integrate traditional inspection data with real-time operating feedback to further reduce downtime and improve safety and efficiency.

Conclusion: The Future of Asset Integrity Management

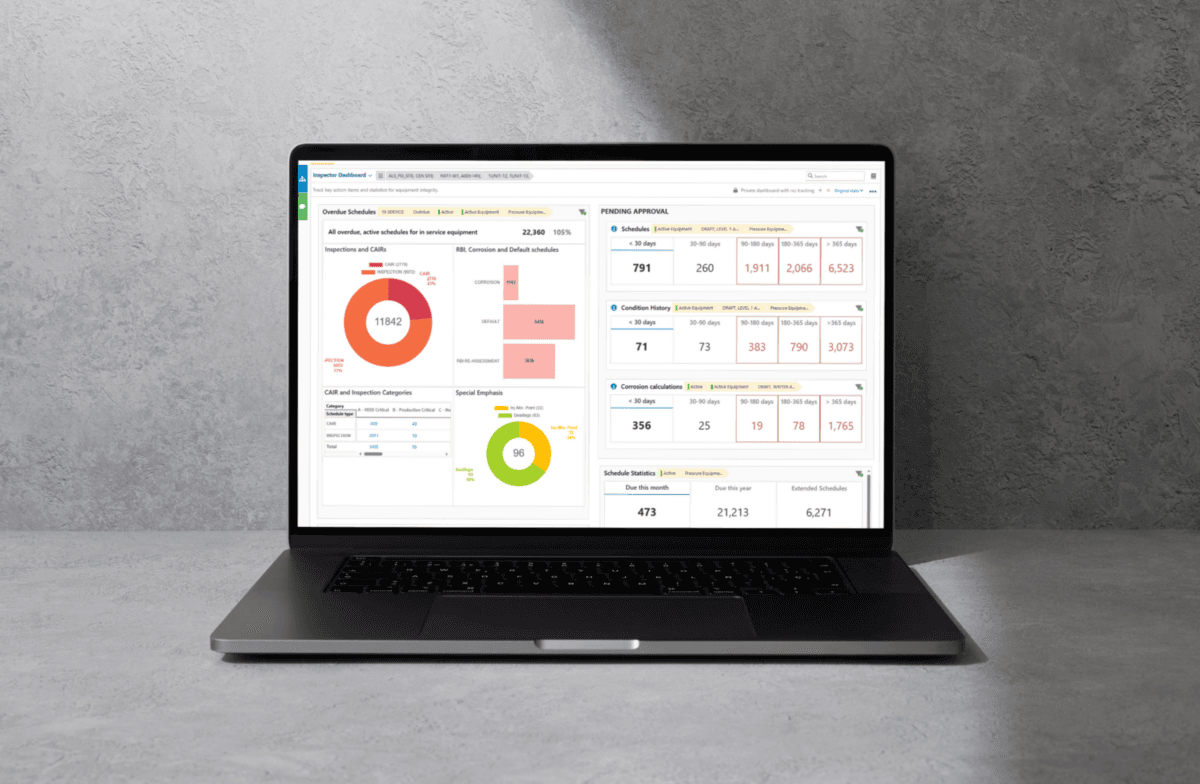

The challenges of managing the integrity of offshore assets are significant, but they are not insurmountable. By embracing a proactive and data-driven approach to Asset Integrity Management, operators can effectively manage the risks of degradation, ensuring the long-term safety, reliability, and profitability of their facilities. The future of AIM lies in the integration of advanced inspection technologies, predictive analytics, and sophisticated software platforms that can provide a holistic view of asset health and performance.

At Cenosco, our IMS Suite exemplifies this integration, helping clients achieve excellence in Asset Integrity Management. The IMS Suite is a comprehensive, integrated software solution that empowers operators to manage the integrity of their assets with confidence, from topside to subsea.

Are you ready to elevate your AIM strategy? Explore how our tools can transform your operations – contact us or visit our resources page.

Prêt pour une démonstration ?

Êtes-vous prêt à voir la suite IMS en action ? Remplissez le formulaire ci-dessous pour réserver une démonstration !

Tomislav Renić Technical Writer

Tomislav is an experienced engineer and technical communicator with over 20 years in complex systems, modeling, and project management. As a Technical Writer at Cenosco, he translates engineering concepts into clear, user-friendly documentation for software in the oil, gas, and refining industries.